Chapter 1

Time at night is different than time in the light of day. He could control time in the light. Not incandescent light but real light. Even daylight confused by fog could be handled. He found a bedroom lamp as frightening as any intruder. Sometimes the darkness was safer.

And so it was tonight. His head ached, the strain of trying to sleep wearing on him, the pain dull, a hammer face pushing on his forehead above his right eye. The Jack and water was not helping either. The effects of his drinking and dreaming, kept his insides frozen, his head hot, his nights restless. How stupid and pathetic he had become.

There was no knowing himself anymore. He sometimes felt poor, ridiculous for a man with lots of money, an airplane and a big house. His heart felt as empty and dark as his house. He was fifty-one years old, felt older, was successful yet failed in his marriage, now divorced and alone. He tried to understand his feelings. By all accounts he was lucky, but it was not the kind of luck that made him feel good, in fact it made him feel bad, especially of late. Years ago this feeling began to press against him, made him uncomfortable with himself. His walks with his old dog were session he used to deal with these feelings of guilt and inadequacy. From damp April evenings to crisp, bright Saturday mornings in October, they tried walking out his issues but only gained the exercise. He was unlucky with answers, not knowing why he was who he was and not someone else. Someone unlucky. Now he thought he knew what to do. He must take his search elsewhere.

Fate stepped in to make him believe a nun had the answer. A woman of God and he needed to meet her. Only he believed this nun could tell him what he needed to know about the life he’s been living. Friends and family thought he had gone over the edge. He believed it. It is the answer he needed to a question he chased around most of his life, and that answer is with her over there. The years he spent searching he now saw as futile; searched in the wrong place, talked to the wrong people. Now he knew where to go and how to get there. It wouldn’t be easy but he welcomed it.

There was now this belief, a correctness to what he was thinking, to his plan. The indecisiveness, the concern, the weight of not knowing, had been lifted from his shoulders. Things had fallen into place. He knew who to ask. He knew where to look. She was what he needed, the little toy at the bottom of the cereal box.

***

Hanley Martin fiddled with the old cargo net, the fiddling a balm, a necessity, like working beads, keeping his mind focused on something other than the conversation he was having and his trip across the Atlantic next week. The trip would be dangerous but so was the conversation he was having that moment. Rocky looked good, he thought, smelled good too. Damn her, she’s not playing fair; women, by nature, he believed, weren’t fair; how could they be?

Rocky said, “I think you’ve become infatuated with her or fixated, whatever. You see her as your savior, almost mythical. The mythical Sister Marie Claire. You think she’ll tell you what you need to know, answer the big question. She doesn’t have the answer. For years you’ve wondered how to pay this great, cosmic debt you owe for your luck. You don’t owe anyone anything; you’ve earned your success. You’ve worked hard. There is no answer. She certainly doesn’t have it. She’s just a nun, that’s all she is, you know. A lonely old woman living in the bush in southern Sudan. I wish you had never heard of her.”

“She’s not that old,” Hanley said, trying to not so gently correct her. “She’s younger than me.”

With a course black thread as heavy as a strand of dental floss, Hanley mended a weak spot on the border of the netting, which, once fixed, would stretch across the cargo hold of Hanley’s old, meticulously restore Beech C-45, the plane he would hop-scotch across the Atlantic to Europe and then on to Africa.

Rocky Vicenti, Hanley’s next door neighbor, his widowed lover, sat on a folding chair in his large, dimly lit hanger facing him as he sat on the steps that formed the interior wall of the plane’s cargo door. It was March of 2001 and unusually cold in north-central Indiana. The hanger was built to house two planes and had, before Hanley crashed when landing at the Russiaville Airport outside of Kokomo almost six months earlier.

“Elizabeth called me again yesterday, the third call this week. She’s desperate you know. She thinks I have more control over you than she has. She’s begging me to make you change your mind. She cries every time we talk,” Rocky said, rubbing her left index finger with her right thumb. Hanley watched her as he passed the curved needle back and forth through the fabric, his finger sliding dangerously along the metal toward the point when the needle met resistance. “What did you tell her,” he ask?

“I said what I always say, ‘Your father has made up his mind and no one can change it, not you or me,’ that’s what I told her. I wish I had something else to say to her but I don’t. I wish I had something else to say to you. I’ve run out of things to say. Obviously ‘I love you’ isn’t good enough,” she said.

“You don’t need to say that. Listen, we’ve been through this enough. Elizabeth think’s I’ve lost my mind. I’m sure her mother has helped her with that decision,” he said.

“I don’t know what to say anymore, really I don’t. You’re going to go no matter what anyone says. If your uncle were still alive I’d call him to talk you out of this but he isn’t and he’d probably support you in this decision. He’s the one that told you to always pay you debts in this life anyway. Did he use the word Karma when he told you this?”

“Please don’t.”

“Really? It doesn’t matter. You’re leaving to find another woman to help you understand life. I’m afraid you’ll travel ten thousand miles to learn she can’t tell you anymore than I can. The trouble is, to sit at her knee or where ever you’ll be sitting, it will still be in a place that can kill you. Maybe that will be enough payment for you. I’ll be left to try to explain that to you daughter and granddaughter. Thanks for that,” Rocky said.

***

Hanley watched the odd cocked rectangle of sunlight slide across the cement, a shape clock, pushed by the sun’s own burning time, admitted to educate him by the open man door of the hanger, the smaller next to the larger door used to take his plane to the tarmac, then the runway, then into the sky and to wherever he wanted. It was an expensive hobby, the plane an expensive toy. He loved things of beauty, whether a meticulously restored airplane, a finely crafted table, a watch or a women. He loved to look, the shiny skin of the Beech, polished, reflective of both his money and his loved of beautiful things, a mirror of this time of his life, the image there, distinguishable but flawed, no straight lines, no hard information, connected shapes, colors, post-modernistic life imagery that everyone saw differently. But the smooth skin of a women reflected nothing back at him. A women was that mirror he must to look at, knowing he would never see himself looking back, his image lost time and again. Hanley considered the conversation the past few minutes, the time spent with Rocky. It had told him nothing.

***

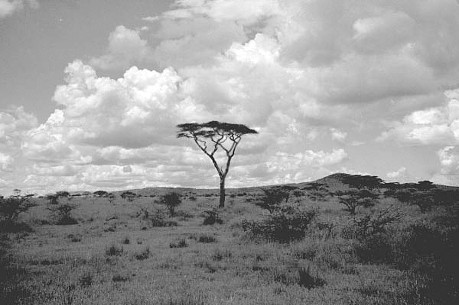

In the distance was Africa. Hanley Martin could see a deeper haze, gray melting to brown, beneath which lay Egypt. The land before him was the vision he had in his head for two years. That vision would certainly not be the reality. Leaning forward, he stared hard at what would soon become familiar and yet remain a mystery to him. He had given up much to be here at this moment and he still wasn’t certain why.

He would enter Africa through Egypt, but his destination was Sudan.

The plane, the noise, the squawk of the air traffic controller in his ear, the vibration of two four-hundred and fifty horsepower Pratt and Whitney R-985 engines coming through the steering pushed their way back into his head. The big engines thrummed, pulsing, grabbing air, pulling the old Beech C-45 Expeditor toward the coast. Hanley Martin thought about what he was about to get into. He smiled slightly and said aloud, “What have you done?”

Ground haze obscured the coastline as Hanley approached Northern Africa. He began searching the coasts for landmarks. The late morning sun reflected off the blindingly polished aluminum skin of the plane, causing glints of light to bounce around the cockpit, off the crystal of his sport wristwatch, up to the surface of his sunglasses causing him some momentary visual disorientation. The nose of plane was painted a flat black, extending up to the cockpit windows, reducing the glare of the bright sun at altitude.

The Beech cruised at one hundred and seventy-five mile per hour. At eight-thousand feet, Hanley could fly with his cabin unpressurized for hours at a time; enough to hop between Crete and Egypt. When distances permitted, he’d been doing that since leaving Kokomo, Indiana three weeks earlier. Hanley found flying an unpressurized cabin less tiring, keeping him more alert.

Turbulence bounced him off the seat. He tightened his grip on the old black bowtie-shaped yoke. The Beech maintained its trim through the mild turbulent air over the Mediterranean Sea. Checking his fuel, then his manifold pressure and his air speed, he reached for the red-knobbed throttle levers and pushed them forward, reducing his speed, adjusted his flaps and started a slow descent.

Seeing the continent for the first time thrilled him more than he expected. He was in it now, he thought, pumped-up and scared at the same time. It caused his gut to tighten a bit just thinking about it. Before leaving Kokomo, Hanley spent some time talking to people who had business dealings in Africa, one man in particular that Sister Mary Kathleen put him in touch with. His name was Bobby Stein. He supplied oil companies with replacement valves and seals. Dealing primarily in Ethiopia and the Mideast, business was good for a while, but local politics caused too many problems. Bobby Stein switched his focus to the countries of the former Soviet Union. While certainly no picnic, dealing with the local Russian criminal element beat dealing with radical Muslims by a mile, he told Hanley. He rated doing business internationally at a three or four out of ten, he said. Doing some business outside America allowed him to keep his contacts in place and active. He explained that he at least hoped to create some balance as a hedge against the ever-increasing ups and downs of the American business cycle.